Books are not letters personally addressed to you, except when they are collections of letters addressed to you. Yet, it sometimes happens, if you’re lucky, that a book or the words within it talk into your ear, with such immediacy -it feels personal. It is as if the writer knows you. Maybe, the writer is having a chat with you, but it’s probably a one-sided chat, and he or she is doing all the talking. You might feel that you could talk back, but you don’t want to miss anything, so you stay silent. And anyway, it could be years before you can think of a good reply.

I don’t remember books I read in my early childhood. Or, maybe I do, but it would need a lot of mental archaeology to rediscover them. From the age of 12 or 13, it was different – there are stories and books I remember very well, and sometimes it’s because a writer seemed to speak directly to me. Ernest Hemingway was one of those writers. His stories got into my mind and directed my thoughts – to the banks of a clear stream with pebbles in it; or, I was sent walking along the pine-needled floor of a great forest, alert for the crack of a twig- a sign of wild deer or an enemy soldier. Those were stories with heartbeats so powerful they brought my own heartbeat in tune with theirs.

The major facts of Hemingway’s life suggest enough material for many stories. He was born in July 1899, in a place called Oak Park, near Chicago. He died in July 1961, just a few weeks short of his 61st birthday. He shot himself. It was his third suicide attempt that year. He had been receiving electro- shock treatment, for depression.

In the First World War, Hemingway was a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy. He was injured and sent home to America. He received awards for bravery from the Italian and American governments. While recovering from his injuries, he suffered from insomnia and had very bad nightmares. He became a reporter for newspapers like the Toronto Star; and he began writing short stories, developing his unique style of writing (I’ll come back to that). He moved to Paris and met other important writers, including Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. Travelling to Spain, he encountered bullfighting and wrote about it. Later, he would write about the Spanish Civil War. He wrote more short stories, novels, and memoirs. And, in the Second World War he was a war correspondent. In 1954 he won the Nobel Prize for literature. He was married four times; and had three sons. (1)

The most controversial aspects of his life include his love of bullfighting and big game hunting. At first, I had no strong opinions on either of these activities. Yet, I felt uneasy reading about some of the gory details. Later in my life, I came to hate violence and cruelty against animals, and I decided that there is no justification for killing animals for ‘sport’ or in the case of bullfighting, for ‘art’. My attitude to Hemingway changed, from something like awe at his writing, to -disappointment, sadness, and confusion. How could I respect a writer who seemed to celebrate behaviour I found abhorrent?

Hemingway’s literary achievements, including – some of the finest prose ever written, and his qualities as a person, including his deep anti fascism and siding with the oppressed, perhaps do not entirely cancel out, on some moral scale, his love of bull fights and killing animals. Yet, he grew up in in a time when most people saw things differently from the common viewpoints we hold today. So, it’s not always a simple matter of good and bad. It’s sometimes more a matter of trying to understand how a mix of good and bad qualities can change over lifetimes, as those things we view as: good, bad, right or wrong – evolve, and our understanding of the world around us changes.

It would take a longer essay to fully grapple with these complicated issues. Perhaps, it’s enough here to say – Hemingway is a troubling writer for many readers. Yet, I believe that his work remains worth reading. My acquaintance with his writings began in a small library in secondary school.

One summer, as I sat in squares of sunlight at a table in the school library, and the rest of the class also lounged around reading or pretending to read, under the vague supervision of some unremembered teacher, I opened a book of short stories. The attraction for me was that several of the stories were very short and I liked the authors’ name: Ernest Hemingway. When I skimmed through the pages of the book, before I took it across to the table, it looked like I would be able to understand all the words. So, back in my seat, I read a few pages, letting the background sounds of my classmates fade away: occasional coughs, whispers, the mix of – fast, loud flicking of pages, and the slower and softer page turning by fascinated readers. I allowed the reading in my head to take control. And I was hooked by the stories about ‘Nick’- home from war and gazing at streams, and there’s a sense in the stories – that he feels intensely alive but he is also lost, although his feelings are rarely directly mentioned. And there was a riveting story about a man waiting in a room to be found and killed by gangsters – The Killers (1927); and there was this opening paragraph of a 2-page story called Old Man at the Bridge (1938), set during the Spanish Civil War:

‘An old man with steel rim spectacles and very dusty clothes sat by the side of the road. There was a pontoon bridge across the river and carts, trucks, and men, women and children were crossing it. The mule-drawn carts staggered up the steep bank from the bridge with soldiers helping push against the spokes of the wheels. The trucks ground up and away heading out of it all and the peasants plodded along in the ankle deep dust. But the old man sat there without moving. He was too tired to go any further.’ (2)

This is a good example of Hemingways’ famous ‘style’. The clever use of simple words. The carefully chosen visual details, accumulating into a picture rich in drama – in this case, of people cast aside by a war. Note the sentence: ‘The trucks ground up and away heading out of it all and the peasants plodded along in the ankle deep dust.’ A concrete detail of one place and one time becomes a powerful motif for the fate of all civilian populations in war, left behind in the dust. And there’s no need to use words of feeling because the feelings are there – in what is happening.

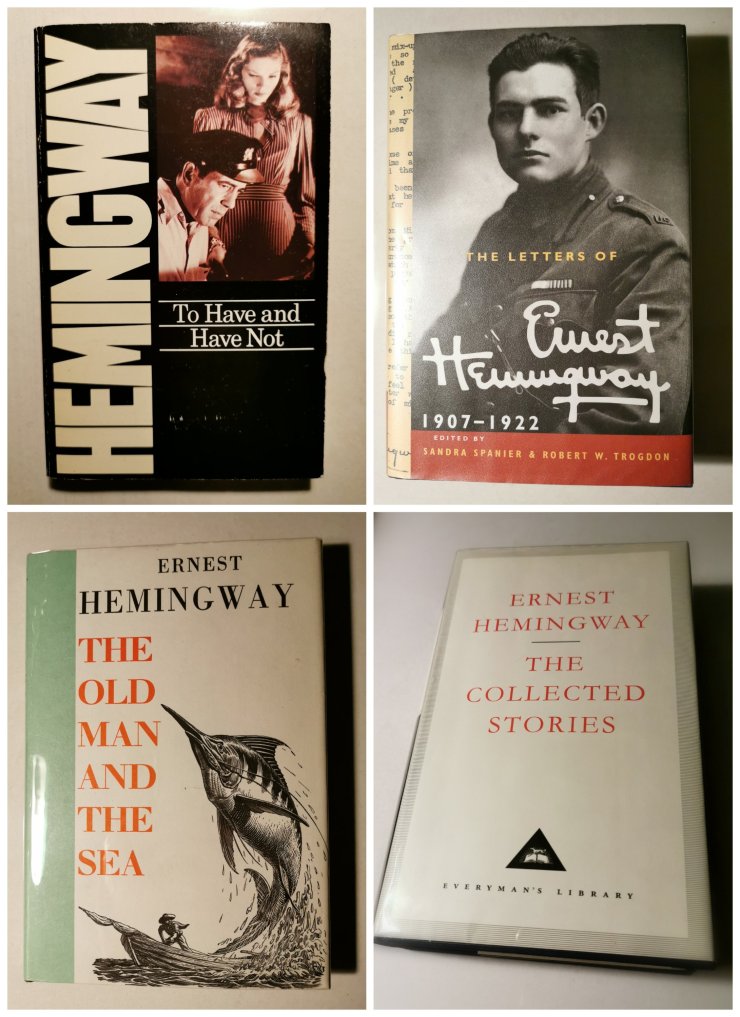

After I read the first story, I had to read more, and within a few weeks, I’d read all of Hemingway’s short stories, or all I could find, and I started on some of the other books. Memoirs : Death in the Afternoon (1932), about bullfighting in Spain, and A Moveable Feast (1964), about becoming a writer in Paris in the years after the first world war. A few of the the novels: For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), set in the Spanish Civil War; To Have and Have Not (1937) – about a Martinique fisherman – a character perfect for Humphrey Bogart to play, as he did in a 1944 movie, alongside Lauren Bacall; Islands in the Stream (1970) – about writing and deep-sea fishing; and the short novel (or novella): The Old Man and the Sea (1952). It won a Pulitzer prize in 1953 and was mentioned by the judges who awarded Hemingway the Nobel Prize in 1954.

I could quote many more paragraphs from Hemingway’s stories and books, or perhaps – some of his journalism – especially the war reporting, or some of his letters, or parts of Ernest Hemingway, A Life Story (1969) by Carlos Baker; and then, it may become clearer what I mean by the power of his writing, and how it grew out of his life and times. Yet, it’s perhaps more useful, to simply suggest – you should read the stories and the books he wrote. Then, you may be drawn into a kind of storytelling which never grows old because it is so full of life. And I’ll allow myself one more quote. This is the opening of For Whom the Bell Tolls:

‘He lay flat on the brown, pine-needled floor of the forest, his chin on his folded arms, and high overhead the wind blew in the tops of the pine trees. The mountainside sloped gently where he lay; but below it was steep and he could see the dark of the oiled road winding through the pass. There was a stream alongside the road and far down the pass he saw a mill beside the stream and the falling water of the dam, white in the summer sunlight.’ (3)

- There are many chronologies of Hemingways’ life. I mainly used the one in ‘Ernest Hemingway -The Collected Stories’ (1995)

- ‘Old Man at the Bridge’ (1938), pp455-456, in the Collected Stories referred to above.

- ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ (1940), the paragraph quoted is the opening of Chapter One.

Nice one Harvey.

The opening description of “For Whom…”, with its patient – even slow – capturing if place reminded me of the start of Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men”. Like a drawn out “Once upon a time…” the reader is taken from their present to the land of the story.

I also think of the intimacy that exists between writer and reader…when I see this …

“Those were stories with heartbeats so powerful they brought my own heartbeat in tune with theirs.”

LikeLike